It was an evening in the middle of August. Jack and Hazel were sitting outside Jack’s house.

It had been a summer they would remember – long days in the familiar countryside, afternoon barbecues and nights of adventure in city pubs and bars. But it was nearly over, and once it was something bigger would be over too.

New chapters were beginning, and to make space for them old chapters had to end.

Neither had mentioned it because saying it made it real and it was almost too much to bear as it was.

The future sat between them like heavy weight.

Jack would go to Durham to read history; Hazel would go to Nottingham to study medicine.

They’d message each other all the time – to begin with at least.

And they’d see each other again – lots – in the breaks between terms and perhaps even weekends visiting each other in their new lives. There’d be Christmases when their families were all together in Willerby.

There were good memories to come but something precious would be gone forever.

Their chain of years, reaching back to before they were born, would be broken – links forged in an infinity of shared moments severed forever. Their easy intimacy would no longer be the anchor of their lives.

An era was passing.

But they still had the evening, warm but cooled with a breeze, bathed in a scarlet and gold heartland sunset stretching over the shallow rolls and folds of the landscape and all the way to forever.

Then it would get dark, and they’d have until dawn for a last night of ghost-spotting together.

“Remembered the binoculars?” Hazel asked.

“Yep, in here” said Jack, lifting a small backpack by its straps, “What have you got?”

Hazel grinned at him, hefting her fuller and bigger pack back at him, “A picnic, wine, weed and a surprise! I’ve had it ready for weeks.”

Jack lay back on his deckchair, looked up at the sky and then at the road. He checked his watch. “Any minute now.”

Hazel hunched forward on the edge of her chair and craned her neck to see round the bend in the road. “Any minute now.”

Right on time, just before ten, the black Daimler rolled round the corner, heavy and assured, polished black paintwork and chrome fittings gleaming in the last of the dying sun’s rays.

Its leather roof was wound down and its driver and passenger – a young man in evening dress and a young woman in a midnight blue ballgown - were laughing at a shared joke.

“Here we go,” said Jack, already swinging his long legs over the mountain bike he’d propped against his house’s walls.

“Yep!” Hazel said, mounting her own bike - and then they were off, keeping the Daimler easily in sight as it purred steadily down the road and towards the junction where Willerby joined the old estate.

Tipsy and flirting, the couple in the car were oblivious to the teenagers following them. They were happy, talking and laughing about how bad the opera they’d just left had been and gossiping about a couple who should have made more of an effort not to be seen out together.

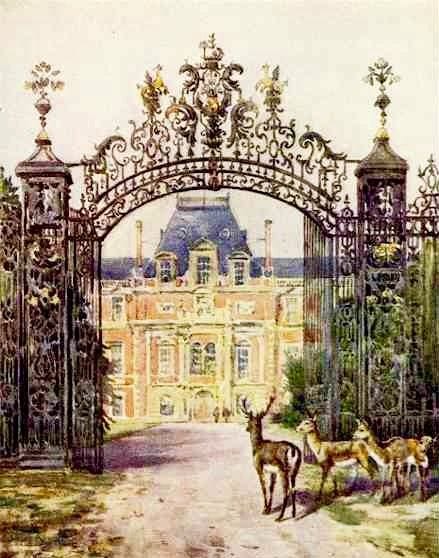

At the junction the car pulled into a queue that began on the road and continued all the way down the long, curving parkland drive that ended up at the gates of the old Meadow Manor House.

The queue was moving so slowly they could overtake the cars.

Jack especially loved these – the Jaguars and Bentleys, the Rolls-Royces and Alvis’ and other makers he’d not heard of until he looked them up; the long bonnets and huge grills, the running boards that swept the whole length of the cars, and how the deep greens, burgundies, and blues of their paintwork shone heavier and deeper than the muted greys, whites and blacks of modern cars.

Hazel was more interested in what the people in them were wearing; women in flowing gowns with ruffled pleats, their hair up in curls that showed off jewelled earrings and pearl necklaces, and men in dark suits and tuxedos wearing top hats and trilbies.

The drive was lit on both sides by a river of coloured lanterns on spikes driven into the ground, their faces covered with ornate grills that turned them into fantastical creatures – unicorns, dragons and phoenixes glowing in the gathering dark. Suited waiters moved up and down the queue pouring glasses of wine and passing cigars through wound down windows.

There was music –piano, saxophone, guitar, bass and drums playing jazz coming from a manor house, which came into view as Jack and Hazel cleared the first sweeping bend in the drive. It was huge and square, a tower at each corner with each of its many windows lit so brightly it was as if it were itself a lantern and its walls a frame built to case an orb of light.

It sat in a garden of topiary hedges and formal flower beds with a maze laid out to the side, also festooned with coloured lanterns.

Jack and Hazel followed the drive until they were close enough to see the wrought iron gates and the liveried doormen checking the invitations of the guests before waving them through.

They could not go further.

They’d tried before - by sneaking through the gates behind a car - but when they did all the lights went out and after an instant of shocking cold found themselves standing alone in a dark field with a modest 1960s chalet at the end of it. Going back through the gate the way they came restored the night to light and music but rules they didn’t understand meant that world could only ever be seen from a distance.

So instead, they left their bikes next to a tree, then took a narrow footpath to the top of the hill where a bench overlooked the house and gardens.

“Ah, just look!” Hazel said.

From above the lanterns and the headlamps of the queuing cars laid the road as a river of light and the house and gardens a fairytale palace.

Hazel sat down. She laid a tartan blanket out and took out a bottle of wine and two glasses from a wicker picnic basket. “Here,” she said to Jack, and passed him a neat joint.

For a few minutes they smoked and drank and looked down at the house and listened to the jazz without saying anything.

All the light made it easy to see the people milling around the garden– most had drinks in their hands and lots of couples were dancing, the men jacketless and many women without their shoes.

“Quick!” Said Jack passing Hazel a pair of binoculars. “The drunk man is about to fall in the fountain.”

When he did, going over backwards with a splash and entirely submerged for a moment before he popped up again, Jack and Hazel burst out laughing and the joint meant they couldn’t stop.

“It’s so funny every time!” Hazel said. “And how many times have we seen it?”

They stopped laughing. “I don’t know,” said Jack. “It all sorts of fades into one, doesn’t it?”

“Yeah,” Hazel said.

For a minute or so neither said anything.

“We’ll forget all this, you know,” said Jack. “Soon. Once we move away. Everyone does.”

“Yeah,” said Hazel. “But tonight, that doesn’t matter, and anyway, everyone forgets everything in the end. Let’s not think about it. Do you want to see my surprise? Turn around and don’t look until I say.”

Jack turned around and there was a rustling from behind him.

“Almost ready,” said Hazel. Then a few moments later, “you can turn around now.”

When he did Hazel was in her prom dress – long, a midnight blue that exactly matched the gown worn by the woman in the Daimler. “How do I look?” She said, grinning.

Jack smiled back “You look great,” he said. “Is that the surprise?”

“Part of it,” Hazel said, “but it’s your turn now. I brought your tuxedo!” She handed him a plastic carrier bag. “Go on, you get changed now. I didn’t bother with shoes. They’re too heavy and it’s too hot for them anyway.”

She sat on the bench watching the house while Jack changed.

He sat down next to her.

“Will you dance with me?” Hazel asked.

Jack didn’t know many steps and was embarrassed to begin with, but as they both got used to moving together under the now dark sky, he realised it didn’t matter. They swayed and leant in against each other, giggling when one of them tripped on the uneven ground and pausing every now and again for wine and later bread, cheese and olives. Below them the partiers danced too and later – in the early hours – the band moved onto the lawn in front of the house. The noises the guests made – shouts, laughs and delighted screams, drifted up easily above the music and in the hot still air and what they said was easy to hear.

“No! Go on!”

“He didn’t!”

“I love this song!”

“As if you’d dare!”

After they got too hot and tired to dance, Jack and Hazel lay back on the blanket, their heads close together and shared memories of their Willerby childhood, of the friends they’d had who’d moved away, all the fetes and parties, the informal village games of cricket played by the children outside the pub that their half-cut parents joined in with. They talked of the future too – about their plans for the long years that stretched out in front of them; where they’d live and travel, the sorts of people they wanted to marry – all their hopes and dreams they knew were safe between them.

“It’ll all burn soon,” Jack said in a quiet moment. “Even though I know I always hope this time it won’t.”

Hazel sighed. “Yeah,” she said. “It will but in the big scheme of things it’s not a bad burning, is it? Nobody gets hurt and without it, I don’t think we’d be seeing any of this. It’s the thing that stamps it.”

Jack shrugged. “Yeah, I know,” he said. “But it’s still sad.”

“Yeah,” Hazel said. “Yeah, it still is.”

The fire started in the house’s kitchen.

To begin with just smoke, then tongues of flame from the window no brighter than the lamps. It spread fast and within half an hour the fire emptied all the guests onto the lawn by the band, which stopped playing to watch too. They stood mostly in small groups and couples with solitary figures scattered between them, all watching as the tongues spread and joined together until the whole building was ablaze and the roaring of the flames drowned out all other sound. Once the roof caught the fire became an inferno so hot it drove the guests further and further back until they were out of the garden altogether and in the parkland around it.

As they watched the house burn Hazel slipped her hand into Jack’s. “Almost time to go,” she said. “It’s starting to get light.”

“In a minute,” said Jack. “There’s a thing I want to do – come with me.”

Holding her hand Jack led Hazel to the oak tree that overhung the bench. He thought about asking Hazel to use the torch on her phone to give him some light, but it was later than he had realised, and he could see well enough in the dawn light. Forgetting he’d changed clothes he reached in his pocket for the penknife he’d brought, laughed and fetched it from the bundle of clothes by the bench.

“What are you doing?” Hazel asked.

“Not much,” he said as he walked back over. “Just this.” Then with careful quick movements he carved their names into the tree. “Jack and Hazel, Forever,” he wrote.

“Ah, that’s nice,” Hazel said. “But it’s missing something,” she took the knife from him and carved a neat heart around their names. “Perfect.”

For a moment neither said anything. Then at the same time they sighed, which made them both laugh again.

“Now it is time to go,” said Hazel. For the last time she turned back to the burning house, which had already faded so much the red dawn in the East was brighter than the flames and the birdsong louder than the flames.

Still holding hands, they walked back down the path and to their bikes. The road was clear – the cars all gone, and the lanterns just hanging pinpricks, lost in the rising sun before they turned off the drive.

When they got back to Willerby it was morning.

At the top end of the village, David looked up from working Bal’s allotment. He was bent over in dungarees and a battered felt hat watering vegetables before it got too hot.

“You two are up early,” he called at them, then stopped as he noticed what they were wearing. His face froze for a moment, as if he’d half-remembered something familiar he’d forgotten, then creased into happy wrinkles. “Ah no – I see. You’re back late. Ghost-spotting, right? Good for you. See you around.”