“A ghost story? In Willerby? Where to even begin?” David said.

“Take it however you like,” said Dan. “Tell us something we don’t know but you think we should.”

“Ah, go on, David,” Mauve said, “there’s time enough before midnight.”

David sat back in his rocking chair by the white Aga and thought for a moment.

“Mind goes back to all the other New Year’s Eves,” he said, “a thin a time as Christmas Eve and thinner still than Halloween which feels less of a thing each year.”

“It’s all the silliness that’s done that,” said Mauve, “you know the costumes, the pumpkin patches – all the modern nonsense.”

“That might be good, no?” Sally asked, toying with her wine glass.

“Hmph,” said David. “Maybe and I don’t want to spoil your fun – I know how much Sammy enjoys his trick-and-treating but..”

“But what?” Sally pressed him.

“The power don’t change – you turn down a flow in one place it’s got to increase in another to keep a balance. It’ll always even out. Thicker on Halloween – thinner at another time; Winter Solstice or Midsummer, equinox or some other time.

“Tell them about the tapestry,” Mauve said, “tell them about that new year. There are new people moving into Willo House next month, so it’s a story they should know.”

David looked over at his wife and nodded. “Right you are,” he turned to look Sally and then her husband Dan, “it were a long time ago now – early eighties. We were young then. Younger than you two are now and still without children. We were so excited to get an invite to that party.”

“Ah yes,” said Mauve, “us not long married, you all handsome in that suit and me all glamourous in a new frock, hair all done, invited by the rich folk who’d bought the grandest house in the village to their first big party. But I’ll let you tell it, David. Go on.”

“There were a few there,” said David, “important seeming folk mostly, the vicar; the Sharps of Sharps’ farm; the doctor who died just a year or so before you two arrived here, and us. I think we were invited because the Fieldings were young too and wanted people their own age there as well as the posh ‘uns.”

“I liked ‘em,” Mauve said, “especially Sophie – she did that posh person trick of telling you what seem like secrets, so you feel they’re a proper chum even though you’ve just met them. She told me right at the start there was going to be a big surprise but not to tell anyone. Even then I knew it were a trick but its charming nonetheless and I didn’t mind and went along. Didn’t even tell you, David, did I?”

“No, you didn’t but it’d have made no difference if you had, we knew even less about Willerby and its ways than you two youngsters do now,” said David. “Anyway, we had a right fancy dinner, lobster and prawns and oysters all laid out on the great table in front of the big open fire.”

“Cigars afterwards too,” said Mauve, “I remember that because Sophie had one and I took one too to show off to her – vile thing – couldn’t stand it really but didn’t let on.”

“It were after that the fellow Crispin told us all about the surprise.”

“Crispin!” Dan interrupted, “you sure you’re not making this up?”

“Crispin it was right enough,” David said, “and I know how it sounds from his name and the big house he’d bought but he was nice enough too. Said he’d teach me to shoot if I wanted to learn and he said it nicely without patronising me and I believe he’d have gone through with it if.. well I’m getting ahead of myself. Where was I?”

“They said there were a surprise for us all,” said Mauve.

“Ah that’s right and so there was,” said David. “They told us all to bring our cigars and drinks and follow them up the stairs, so we all did.”

“Turned off all the lights, remember?” Mauve said, leaning forward and touching David’s arm. “Said it would be more atmospheric – Sophie led us up with an old iron candelabra she said she found in the house’s cellar, throwing shadows on all of them dark wood panelled walls, us all giggling and tripping up the steps behind her. I remember being pleased with myself I’d taken off my heels because the going was uneven and tricky in the dark.”

“That’s right,” said David. “Up we all went in the dark, to the first floor, then the second, then into one of the attic bedrooms. They were decorating and the furniture was beneath sheets and the walls all bare – they’d stripped the old wallpaper I suppose.”

“They’d have wanted something modernish, or modern for then,” said Mauve. “They weren’t you know, fuddy-duddy people.”

“Well, whatever they were going to do they’d stripped the walls right enough,” said David. “That’s how they found the walled-up door in the first place.”

Dan took a gulp of his beer, sat back in his chair and whistled through his teeth.

“A walled-up door upstairs in an old house in Willerby,” he said, “I’d have left that right alone.”

“Says the fellow who went right ahead and had Jack’s Pool dredged almost as soon as he got here,” Mauve said, shooting him a mock angry look, “but yeah right enough you’ve got more sense now – but neither Sophie nor Crispin knew what you do now and neither did we at the time. We thought it just as excitin’ as they did.”

“They’d already knocked it through,” said David, “or most likely got someone else to do it. To rich people – even the nice ones – they think someone doing something for them is the same thing as them doing it themselves.”

“Oh, yes,” Mauve said, I remember it so well now. Sophie made us all wait while she went in. She put the candelabra down and lit some other candles then came back and told us to go in with our eyes closed and not to peek until she said to.”

“You did peek though, right?” Asked Sally.

Mauve threw back her head and cackled delightedly. “Course I did!” She said, “I may have been young but I wasn’t no fool. But I pretended I hadn’t and joined in with all the gasping when she said everyone could look.”

“It were – still is I suppose – a very beautiful thing,” said David, “all gold and bright green glinting in the dancing flames, the blue river and the pond the brightest blue.”

“A picture?” Dan said.

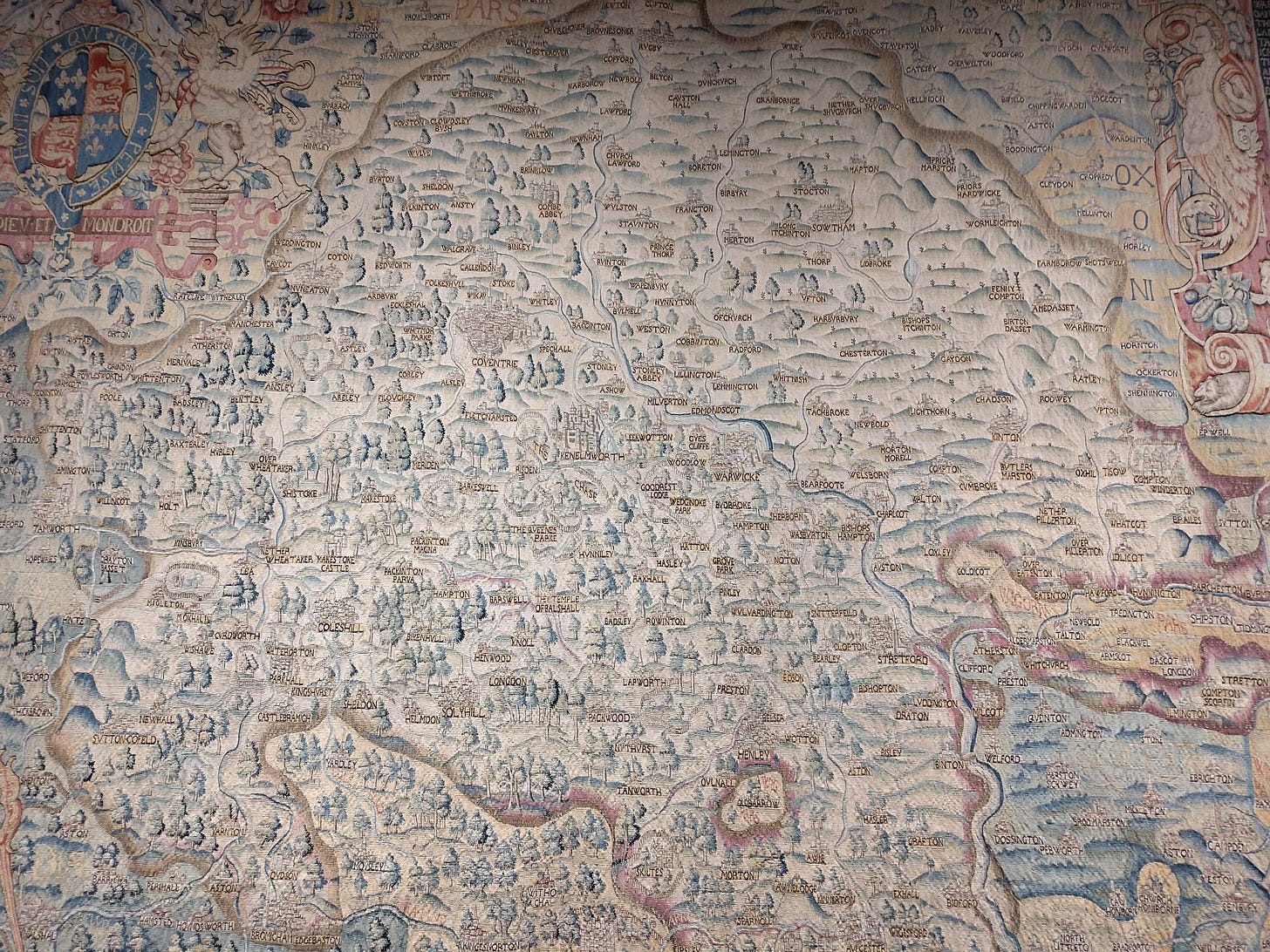

“A map of the whole village”, said David. “Huge. Hung floor to ceiling, all done in stitching so fine and clear you could read every letter even in candlelight. The church were on it and Jack’s Pool – the writing said “Jakk”, but that’s no account as they spelled things differently then, and Willo House right in the centre with all these paths going out from it like inky dark spiderwebs through the hills and the trees.”

“Sophie curtseyed in front of it,” said Mauve, “I remember her doing that like she were in a film or something, saying it was her glorious surprise, then beckoning us all up to have a closer look, telling us it was hers, finders keepers and all, and to keep it a secret so no busybody official could take it away or anything.”

“It seemed to move in your eyes when you got right up to it,” said David, “and if you looked away and looked back you there were always things there you hadn’t seen before – a different stream or hill, forts, little clumps of houses that were almost villages in themselves, puffs of smoke coming from their chimneys.”

“Caves and mountains too,” said Mauve, “and everywhere deer and rabbits and hares, giant snails, fish in the rivers. Dragons.”

“We were all there a long, long time,” said David. “The vicar, he said it must have been done before Henry did his thing because there was an old monastery on it that he closed down, but Willo House was built after that so that had us all scratching our heads.”

“I left them to it before very long.” Mauve said, “there were something I didn’t like about it – the appearing and disappearing everyone said was just the candlelight, and the way it seemed to ripple every now and again, as it there were a breeze that there wasn’t.”

“We weren’t that long after you,” said David, “all of us except poor Sophie who said she’d be down in just a minute.”

“It wasn’t until the clock began striking midnight that we missed her,” said Mauve. “Crispin went up first to get her then came down calling her name. Then we all went searching for her, searched the whole house, thinking it was a joke of hers to begin with or another surprise – expecting her to pop out of a wardrobe or something, then worried, then all scared beyond words.”

“You never found her, did you?” Asked Dan, rhetorically.

“No, we didn’t then. Nobody did,” said David. “I think as soon as the morning came even Crispin knew she’d not be back. He moved away – to London, they said. Moved on, married again, heard he became some sort of very successful lawyer who made a fortune in the 90s from property. Sold up, had that room walled up again and never came back.

After a short silence Alexa suddenly announced, “It’s midnight!” and began playing the Westminster chime.

Sally looked over to the speaker and saw an empty old iron candelabra sitting next to it on the wooden shelf.

“Is that?” she asked.

“Right enough, it is.” David said. “Mauve got a feeling – she got those even then – and smuggled it out in her handbag.”

“It’s old,” said Mauve, “older than Willo House probably and of a sort of working I can’t find provenance for. I’ve a feeling it’s best kept separate to that tapestry. It’s a thing that’ll come to you when we get too old and the time’s right. It might be nothing to do with anything but with things like this – as you know now – it’s always better to be safe than sorry.

…

“Not really a ghost story though was it?” Dan said to David later over whiskey, after the joining of hands and Auld Lang Syne and after their wives had gone to bed.

David fixed Dan with a look. “I said we didn’t find her then,” he said, “but she’s been seen since, in places you won’t find on any map that’s not that tapestry. She’s not pleasant to see. Angry, I think. Sad, I’m sure. Maybe she needs help. Maybe there’s no hope for her or maybe there is. Maybe this is a rare thing Mauve and I don’t agree on. Maybe that’s something for you and Sal to sort one day. But not tonight.”

Very creepy!